Every nobody is a somebody to someone

by Bill Miller for

the Mail Tribune

Monday, January 27th

2020

Most of us are nobody to the rest of

the world.

History is usually only about the

famous people, and seldom do we get the chance to share a few moments of a

common person’s life — those unknown strangers who have felt happiness,

sadness, fear and love just the same as we have.

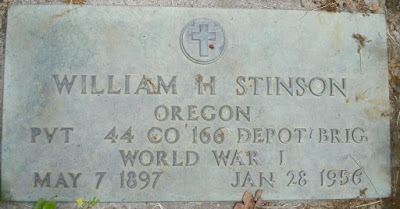

William Stinson died in 1956, and I

wouldn’t have known anything about him if I hadn’t come across a couple of

letters he had written to his mother in 1918. He was serving with the U.S. Army

during WWI.

I wondered if he had left enough tracks

to help learn something about who he was and how he lived life through his 58

years. It wasn’t much.

Born in 1897 on his father and mother’s

farm just east of Roxy Ann, he was the youngest of three children.

It began with William, 20, writing from

Kelly Field, just outside San Antonio, Texas, where he was training to be an

airplane mechanic. After briefly working to help build the COPCO Dam

(California Oregon Power Company) on the Klamath River, he spent nearly a year

at Oregon State College before joining the Army, Jan. 9, 1918.

“Dear Mother,” he wrote. “I don’t have

much time as I am sergeant and have to see to things. I don’t pick up paper and

clean up like most of them do, but I have to oversee it and be sure it is done

right, and I have to call the fellows out in the morning at 6:15 and call the

roll and report to the captain.

“The flying machines here are almost as

thick as birds, and they sure do some flying.”

A month before his 21st birthday, he

was transferred to Hempstead, New York, and was waiting to be sent to France.

Apparently his mother wanted to send him a birthday cake.

“I sure would like the birthday cake,

mother, but I don’t think it will be here. You might send me a small cake any

time, as it doesn’t cost much and they are sure good.”

By the time his unit was ready to ship

out to France, the Armistice was signed, war was over, and the men not needed

anymore. In a telegram a week before Christmas 1918, William said he was

discharged and coming home for good.

The following May he married Katherine

Conser, the wedding said to have been a big surprise for friends and relatives,

but no reason why was given.

William was once again working for

COPCO, his career flourishing as he and his growing family moved from one

location to another.

In 1921, using only a Ford roadster,

some rope, and long poles; he supervised a Medford crew called out to repair a

light pole that had been blown down by a storm and was lying dangerously across

a 4,000 volt power line.

He spent some time in Prospect and then

Grants Pass, before transferring to Crescent City, where he lived from 1928

until he returned to Medford in 1934.

In 1941, Katherine filed for divorce.

The couple had six children.

William remarried and moved to Roseburg

as COPCO’s area superintendent. Still there in 1954, he became severally ill

and transferred to California. There he died in January 1956. He is buried in

Medford’s Siskiyou Cemetery.

William’s was a simple, everyday life,

and for the most part, known only by friends and family, yet for a brief few

moments, it was a life that turned a nobody I never knew into a somebody — a

somebody for me, and maybe for you.

Writer Bill Miller is the author of

five books, including“Forgotten Voices of WWI,” Reach him at

newsmiller@live.com.

https://mailtribune.com/lifestyle/every-nobody-is-a-somebody-to-someone